Litigation Spotlight Series: Bill Ogden shares an inside look into how it felt to receive Alex Jones' texts in discovery, and the strategy behind the “Perry Mason Moment.”

While attending college in Huntsville, Bill Ogden watched Alex Jones on local public radio and television; he never imagined that he would litigate against Jones in the alt-right radio host's defamation trial.

Texas-native Bill Ogden attended South Texas College of Law in Houston and joined Farrar & Ball as an Associate after graduation. Now a partner at the firm, Ogden specializes in representing individuals who have fallen victim to injuries caused by negligence and defective products. In 2018, Ogden began litigating defamation lawsuits against Alex Jones, who spread false claims about the parents who lost children in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting.

Bill Ogden shares a first-hand look into the Neil Heslin et al. v. Free Speech Systems and Alex Jones trial, where the jury awarded $49,300,000 in compensatory and punitive damages. In this interview with the Clearbrief team, Ogden tells the story of the defamation trial that received a great deal of media attention and became the subject of many internet memes.

It's an honor to meet you, Bill! You were in the “room where it happens” for one of the biggest courtroom moments of the decade. Can you start by sharing a bit about your practice and how you came to work on the Alex Jones case?

I am born and raised in Houston, Texas, where our firm Farrar & Ball is located. I went to law school in Houston at South Texas College of Law, and after graduation, I taught there as an adjuct professor. Today, I'm still involved in the mock Trial Advocacy program. While at South Texas College of Law, I was hired as a Summer Associate at Farrar & Ball, and ended up there after graduation. This is actually my tenth year at the firm.

When I started at Farrar & Ball, we were almost exclusively doing automotive defect cases and personal injury work. All of our cases were on Cooper Tire, Good Year, Ford, and all other major manufacturers of car components or vehicles. Those types of cases have tons of moving parts. It's a product liability case, but your products are going 70 miles an hour when it fails. Farrar & Ball was very successful at doing automotive defect cases; to the point where we were allowed to take cases that weren't necessarily going to be for money. We call them “hobby cases.” Then we took the Sandy Hook case.

Mark Bankston, the attorney you might know as the one who revealed the texts Jones' lawyer accidentally sent to Farrar & Ball, is an attorney at our firm. He's probably the best brief writer I've ever seen. He can outwork an entire team of defense lawyers, because of how fast his brain works. Mark doesn't even have to do rough drafts, everything comes out as the final product. We call him our unfair advantage. One day, we were contacted by a young man named Marcel Fontaine. Alex Jones had posted his photo and said he was the Parkland Florida high school shooter. Mark came to my office and said hey, do you want to go against Alex Jones? I said, “Absolutely.” That was the first case that brought us into the orbit of Alex Jones.

I've been watching Alex Jones since I was in college on public radio and public television channels in Huntsville, Texas. It used to be entertainment. Around 2015, Jones realized if he went politically one way or the other, he could monetize his platform a lot more. That's when he really went to the right. It was never political until he realized he could make more money that way. That's when it stopped being entertainment, and it was clear that there was more of an agenda behind it.

When we were contacted by Marcel, we decided we were in. We spent a few weeks brushing up on First Amendment law and Constitutional law. Becuase we do a lot of work in federal courts, we were pretty familiar with these areas already. We figured if we can do cases with complicated areas like biomedical engineering and accent reconstruction, and communicate it to a jury effectively, a defamation case can't be that bad. So we learned it and took the case. It wasn't until the day after we filed the Marcel's case that we realized how much publicity it was going to get. It was on the front page of Huffington Post, and we were in shock. Next, the New York Times called and said they'd like to send their feature reporter out to get to know us.

Soon after, we were contacted by Neil Heslin, a father of a Sandy Hook victim, and we took the case. When the case started, I was one of the low men on the totem pole. I had to go through hundreds of hours of Infowars videos, and oh, it can get to you. It kind of brainwashed me a little bit. Mark came into my office one day he was said “Dude, you gotta take a break. You gotta step away.” It's just because Alex Jones rapidly fires information on so many different topics at any given time. After a while, all of it grinds on you a little bit.

Soon after, Mark Bankston and I were contacted by Neil Heslin, a father of a Sandy Hook victim, and we took the case.

Can you talk about what the discovery process was like?

Texas has a Texas Citizens Participation Act, or TCPA, which is its version of anti-SLAPP statute, meaning you cannot file a lawsuit purely to restrict somebody’s constitutional rights. The attorneys representing Jones filed the TCPA motion, a motion to dismiss. In response, we filed a motion asking the court to allow limited discovery on some of the issues. Not only did we have to ask, but the court then had to approve it because we were in this limited discovery phase. The court did actually approve it and ordered the defendant, Jones, to produce certain documents and depositions. As we now know, they could not have failed that more.

After several complex discovery motions that went up on appeal and back down, the court granted our motion for a default judgment. That meant we would now limit the trial and the discovery to the damages. Because the default judgment was granted and we alleged punitive damages, the court takes what's in our petition as true. That was kind a unique strategy move. Even though it's just a damages trial, you get to talk about all the bad liability stuff because it goes towards the punitive damages.

Can you share a little bit about your experience preparing for the trial in terms of preparing exhibits? Do you use an outline for your questions?

For every witness, whether direct or cross, we have an outline, which I actually learned through the Trial Advocacy Program in law school. We do it very specifically: we don't write out all of our questions word for word, because we never want to read straight off of our outline.

The outline is there during the examination if we get lost, but for the most part, we want to listen to the answer and take the examination where we want it to go. For each area that we want to accomplish, we have bullet points. If we are using exhibits, we finalize the exhibit list, write out the examinations, and then if we're referring to a deposition we put in page and line numbers. We place exhibit numbers in a way that our trial tech or paralegal knows exactly where things need to go. I think the reason why we're most effective in trials is because we're afraid to be unorganized. We're very calculated in everything we do. Nobody walks in and says I'm just winging it off the cuff.

The outline is there during the examination if we get lost, but for the most part, we want to listen to the answer and take the examination where we want it to go.

What role did technology play in helping you make sense of the discovery you received from Alex Jones?

During COVID, I spent a lot of time and money learning about electronically stored information and mastering electronically stored information (ESI) protocols. When you're dealing with different types of cases, you've got millions of pages of documents. We used that in the Alex Jones case because we got 85,000 different documents at one time. Only probably 84,950 of them were useless. They didn't review them. They didn't Bates stamp them, they just sent them to us. Unlike big law firm litigation sections, we were still individually pulling PDFs each time. We were also hosting it all on internal servers, which was a nightmare and expensive. And now I have gone to a number of conferences and done speeches on electronically stored information, saying, “I understand nobody likes to change, especially the older folks in the legal profession, but you're at an unfair disadvantage if you don't learn this and understand how they're using it against you.”

I understand nobody likes to change, especially the older folks in the legal profession, but you're at an unfair disadvantage if you don't learn this and understand how they're using it against you.

We couldn't agree more about the massive advantage firms gain when they leverage tech to sort through massive amounts of discovery to find the gems.

Editors Note: Clearbrief is used to instantly find the relevant source documents to support any statement in a trial outline, and to create interactive exhibit lists.

So, tell me about when Alex Jones admitted on the stand that he lied about Sandy Hook being a hoax. What was that moment like?

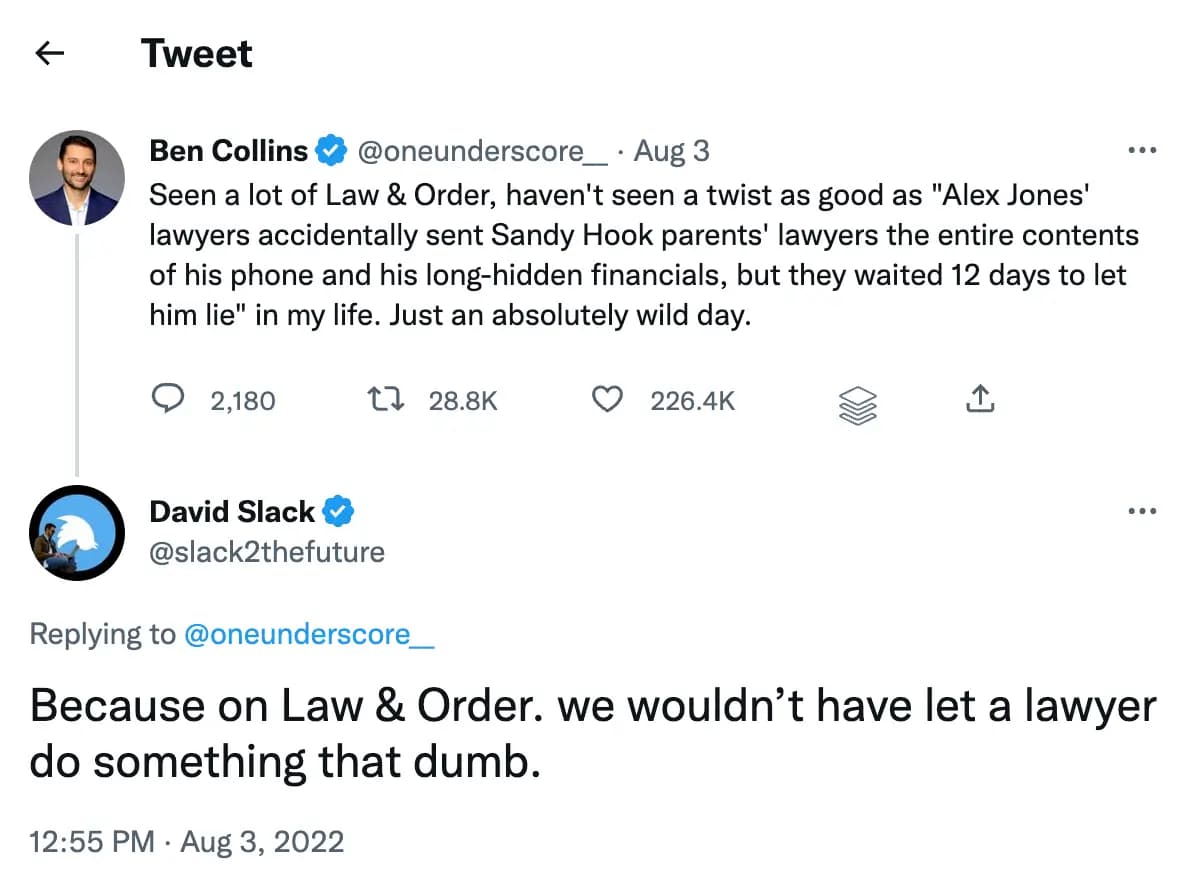

That could not have gone better. Three days before the trial started, Mark and I received an email from the defense. I immediately asked myself, “What are they producing?” When I opened it up, I immediately realized from some of the folder names that we were not supposed to have this. We immediately stopped going through it and sent the infamous email to defense saying “I don't think you meant to send this to us.” The response we got simply told us to disregard.

In Texas, the Anti-Clawback statute is very clear: to pull something back, you have to specifically identify all documents you want back. Since the folder they sent us was so big, the defense basically just said, “oh don't worry about it.” Then we realized there was a folder that had every text message Jones had sent for two years. And some of the names that he was texting with were people that would kind of shock you a little bit. I mean, they were page-turning texts.

But the day we got the text messages we realized what we had. In the deposition, Alex Jones said he searched in his phone with the search bar and nothing containing the words “Sandy Hook” was found. We had to sit there, anticipating.

In Texas, the Anti-Clawback statute is very clear: to pull something back, you have to specifically identify all documents you want back.

Because the Texas Anti-Clawback statute allows ten days to clawback and it had only been three days since the emails were wrongly sent to us, we had to wait seven more days. Once that tenth day hit, we waited for an extra one just to make sure we counted our days right. On that eleventh day we could do whatever we wanted with the texts. The reason I say that moment in court couldn't have been better is because Alex had no clue. When Mark showed the texts to him, he's like I told you, nice try. Mark even started kind of laughing and it felt good. Alex then said we were trying to have our Perry Mason moment, which is when Mark gave what I think is the most iconic courtroom moment of the decade probably, where after he reveals that his own attorney gave him the messages 10 days ago, he asks if Jones knows what perjury is. That's when Alex Jones' face turned bright red, his emotions dropped, and he didn't know what to do.

His attorney was just sitting there, staring straight ahead, not knowing what to do either, because he knows it's his fault. And Mark just told the world that it was his fault. That was a crazy moment that we didn't see coming. Frankly, we didn't deserve it, but it fell into our laps.

In Texas, the Anti-Clawback statute is very clear: to pull something back, you have to specifically identify all documents you want back.

Wow, I can only imagine what it was like waiting those days.

When we started talking about whether or not we were going to call Alex Jones to the stand, we knew he is a wildcard. Whether you agree with what he's saying or not, you pay attention to him because he speaks in a way that pulls you in. We'd already destroyed him through all the experts who testified about the misinformation and how much money he made, so we wondered if we needed it. But we decided to go for it and wait to call him in the punitive phase. To our surprise, his own attorneys called him to the stand, and it was perfect. Now, we know he's gonna say whatever he wants, and try to make everybody feel bad. It played out as the best case scenario for us. It was so good because when you boil it down to cases about hurt feelings, how much is it? How much does it cost to hurt those parents' feelings? $49.3 million is a lot of hurt feelings.

Okay, that was fantastic. What do you have to say about all of the media coverage the trial received?

The trial was only two weeks, but exhausting because every single day something shocking happened on the stand. Alex Jones called the judge a pedophile, our client autistic, and there's even a video of Alex Jones basically calling the jury simpletons. There were just so many bombshells.

Going back to what the jury saw in terms of evidence, what role do you think the experience of seeing evidence like documents and text messages had on the jury?

Afterwards we talked to the jury and the judge for an hour and a half. We knew about the Texas punitive damage cap, and that we had a good argument to get around it, but we didn't want to have to get around it. Our compensatory phase was only 4.1 million, and we were really hoping that was going to be closer to the hundred we asked for. We weren't done yet, though, we had to go back and get an expert for Alex’s net worth. The jury wanted more hard evidence, like photos, pictures, or emails of threats. That was just some of the items to actually show them the damages because there was so much excitement and inflammatory evidence that could only go towards punitive damages.

Why do you think they wanted that sort of visual evidence or concrete documentation?

My theory is when you hear someone pour their heart out on something, and they have such a vivid memory, but then they're asked about something else a month before, and they don't remember, you can start to think, wow, it's almost convenient that you can only remember the stuff that is good for your case. When you show emails and text messages of the harassment you received, it is more real. It has a lot more impact than just words. There's no doubt about that. When we bring in videos, photos, documents, or physical evidence you see the human connection. That's why I don't like Zoom trials, because you don't have that energy or connection. It's much harder to lie when you're staring someone in the eye. I think that's the connection that hits home and gives you a bit of affirmation as a juror. Physical evidence or seeing a visual of it is the biggest tool in getting from sympathy to empathy.

That's exactly the mission behind Clearbrief - to bring transparency to the facts that can make or break a case.

Clearbrief's Word Add-In allows users to instantly create hyperlinks throughout the document with a single click so the sources cited can be easily viewed by the judge, jury, and your opponent, so they see why you win.

To try out Clearbrief, visit clearbrief.com/signup or get Clearbrief directly from the Microsoft App store.

Follow Clearbrief on Linkedin and Twitter at @Clearbriefai.